Breakfast in Civilization Part IV: A Pennsylvania Farming Family in 1800

She is stirred from a deep sleep by the sound of her 4-month-old daughter fussing in the trundle at the foot of their bed. It’s winter so it’s still dark out and she knows their bedroom will be freezing. She reluctantly climbs out from under the pile of wool blankets she and her husband sleep under and shivers in spite of the thick nightshirt and cap she’s wearing. She picks up her daughter and coos to calm her and then carries her downstairs. It’s a bit warmer in the main room of the house as the fireplace is still smoldering under the ashes her husband placed over it before retiring last night. Still holding the baby, she adds some kindling to get the fire going again. The fire is the first order of business as it’s the hub and heart of their lives. She wakes her 7-year-old son as it’s his job to warm the water for their morning wash up. As she changes her daughter, her son adds logs to the fireplace and pours some of the well water kept in the wooden bucket by the fireplace into the pot hanging in front of the fire.

She follows her son upstairs where he pours warm water into the washbasin sitting on the dresser in their bedroom. The family then takes turns washing their hands and faces using soap she made from fireplace ashes, water and used cooking oil. In the warmer months, there would already be water in the basin, but in winter it would freeze so a pail must be kept near the fireplace to be heated up each morning. She prepares a morning meal of corn she popped three days ago in the same pot used to warm the water in bowls with milk from their cow and a bit of sugar purchased at the general store in their nearby town. She makes toast with their last few slices of bread in a rack that toasts the side facing the fire and then rotates them to toast the other. After breakfast she rolls their oven, a simple metal cabinet with three internal racks, in front of the fire so it could start the long process of heating up enough to bake bread and pies when they got back from church.

They’d had a good harvest, especially their beans, corn and squash, and this had enabled them to stock the pantry with enough flour, sugar and salt for the winter. Early Pennsylvania settlers had learned from the Lenape Indians that beans, corn and squash grew well together here. The Lenape, through centuries of trial and error developed this system of cultivation, what they called “the three sisters”, and by sharing it, kept many early settlers from starvation. As more and more settlers poured into western Pennsylvania, the Lenape moved westward, away from the land they’d inhabited for thousands of years.

Even with their fields covered in snow there is much to be done. Her husband will spend his day repairing the hayloft in their barn and portions of fence for which there wasn’t time during growing and harvest season. Their son, now old enough to help out, will milk their cow, feed their chickens and chop firewood. In addition to baking, she needed to churn butter today, not just for the family, but to barter with the general store in town for needed supplies. She also had mending to do and was hoping she’d have time to finish a new night shirt she’s started for her daughter who was quickly outgrowing the one she had.

All of this had to be done before or after taking the wagon into town for church. She always enjoyed putting on her nice dress and getting to see everyone, but she especially loved the hymns. They haven’t sung her favorite “Christ the Lord is Risen Today” for some weeks and she hopes they will today. While she’s grateful for all the blessings the Lord has bestowed upon their family, her life often feels like a constant struggle. The loss of their other son, who would be five if he’d lived, had shaken her faith. Even though God saw fit to bless her with a daughter, she still felt the loss of her son deeply and at times wondered how a loving and merciful God could take her child from her. Their pastor told her that God had another plan for her son and had to call him home. He also told her that God understands her sacrifice, feels her suffering and sees her hard work and devotion. He will one day welcome her through the gates of heaven so she can be with her son again. There are moments when clinging to this hope is the only thing that keeps her going.

Despite her life’s hardships, she does feel truly blessed, but at times can’t help but envy her cousin Mary. Her father and his brother, Mary’s father, had immigrated from Germany together to settle in Philadelphia. She and Mary grew up as close as sisters but when they got married, when she was 18 and Mary 19, they went further west into Pennsylvania to homestead their farm while Mary and her husband moved south to Virginia. She was always excited to receive a letter from Mary, always written in that hodge-podge of German and English they thought of as their private language, but sometimes the stories of Mary’s far more comfortable life in Virginia made her jealous.

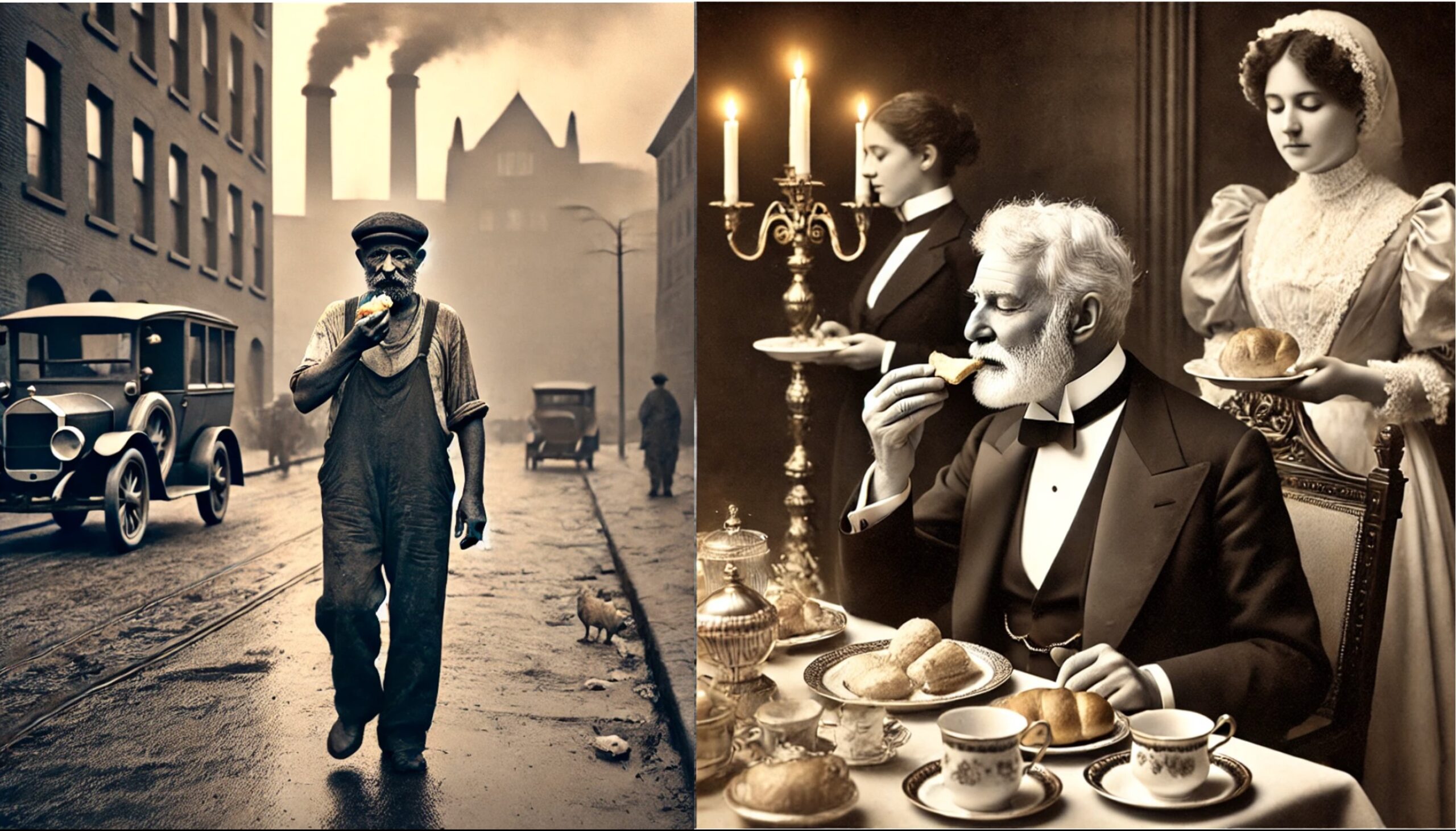

Mary and her husband owned a small tobacco plantation that had done quite well. Rather than working every day to keep the house and prepare the meals, Mary had three slaves, a cook, a butler and a maid, to do her bidding. Rather than toiling in the fields all day the way her husband did, the other six slaves they owned—eight if you count the two young children which had been born in the last few years—handled the bulk of that work. Mary’s husband spent his days reviewing plantation business, riding his favorite horse or gathering with other prominent local men to drink, smoke and discuss the issues of the day. Shocked by some of Mary’s stories, she asked her pastor if the way slaves were treated was truly Christian. Her pastor replied that it was both merciful and Christian to bring them under God’s protection. They were better off as slaves under Christ than Godless savages in the jungle.

She doesn’t know it now, but ultimately it will be she, not Mary, who is the lucky one. Their farm will expand from 20 to 50 acres and once her son comes of age, they will clear out an additional 25 acres for his family. While this farm, and ultimately its land, will be the source of financial security for generations of her family, her cousin Mary’s family will lose their plantation in the Civil War and never truly recover.