Breakfast in Civilization Part III: Thomas Penn & his Brothers in 1737

The following piece is historical fiction. All the characters, apart from the two valets, are historical figures and the events described are things that actually happened.

The sound of his curtains being pulled open rouses him. “Good morning, Mister Penn.” Despite his residual sleepiness, Thomas smiles inwardly at his valet’s use of “Mister.” When Jack first came under his employ as an indentured servant, a four-year sentence for stealing a loaf of bread, it was “Master Penn.” Jack’s initial duties were largely menial, but the pride Jack took in completing those tasks and his eagerness to learn more made it clear to Thomas that Jack saw his sentence as an opportunity to better himself. Thomas took on a more active role in mentoring and ultimately expanding and elevating Jack’s duties. Four years earlier, in 1732, when it was decided that Thomas needed to travel from London to the Colony of Pennsylvania to directly manage the family’s lands and businesses there, he made Jack an offer he never imagined he’d make to an indentured servant; come with me to Pennsylvania, finish the last two years of your sentence and I’ll give you a permanent position in my house. Jack enthusiastically accepted and once his sentence was complete was hired as a footman at Pennsbury Manor, the Penn estate in the new world. At that point, Thomas told Jack that he could address him as “Sir” or “Mister.” While clearly honored by this, some time passed before Jack actually used either of these monikers.

As the health of Thomas’ long-term valet, Edward, declined, Jack, ever eager to learn and advance, began to fill in. When Edward became unable to work, moving Jack into that role full time, along with its substantial rise in salary and status both inside and outside the home, was only natural. Thomas began to feel a paternal pride in Jack’s advancement and a bond formed between them. Nearly a year ago, he told Jack that when they’re alone he could call him “Thomas,” but Jack had yet to do so.

“Breakfast will be served in a half hour. Your brothers are already awake.”

While his older brother John would frequently reside at Pennsbury Manor, having the younger Richard, who spent most of his time in London, would normally be a joyous occasion. He was not, however, looking forward to this breakfast. He knew Richard was here to deliver dire warnings about the fortunes of the Penn family, that all their father and grandfather had built, the life they lived and the prospects for their children and grandchildren were in serious jeopardy. Financial pressures were nothing new, he and John had been selling off land in the new world bequeathed to their father by King Charles II to settle the massive debt he owned their grandfather, but now Richard had sailed an ocean to tell them it was not enough.

He moves toward the large mirror in the corner where the breeches, waistcoat, frock coat and cravat Jack had laid out for him waited. The conflicting nature of Thomas’ position as a wealthy landowner and a prominent Quaker was reflected in what he chose to wear and when. Fine silks and linens with a powdered wig for formal gatherings with other prominent men or more modest, and wigless, dress for meetings with fellow Quakers. This morning fell somewhere in-between as his brothers understood what it was to be an upper-class Quaker. That conflict mirrored the one between their father’s high-minded Quaker ideals that made him so revered and the stark financial realities they now faced. The treaty their father signed with the Lenape Indian Chief Tamanend in 1683 declared they would “live in peace as long as the waters run in the rivers and creeks and as long as the stars and moon endure,” made him a beloved figure but said nothing about what was to be done if the money ran out.

“Is what I’ve selected satisfactory Mister Penn?” Again, Thomas smiled inwardly at this daily bit of theatre. Jack asked this question every day and every day each item would be both perfect for the occasion and perfectly cleaned and pressed. It was remarkable to Thomas that Jack, who grew up in a London slum, could develop such an understanding of these fashion intricacies. He recalled his father once saying that African slaves were “more dependable” than indentured servants and while Thomas found this often to be true of the slaves he inherited from his father, as well as their offspring, Jack was a notable exception.

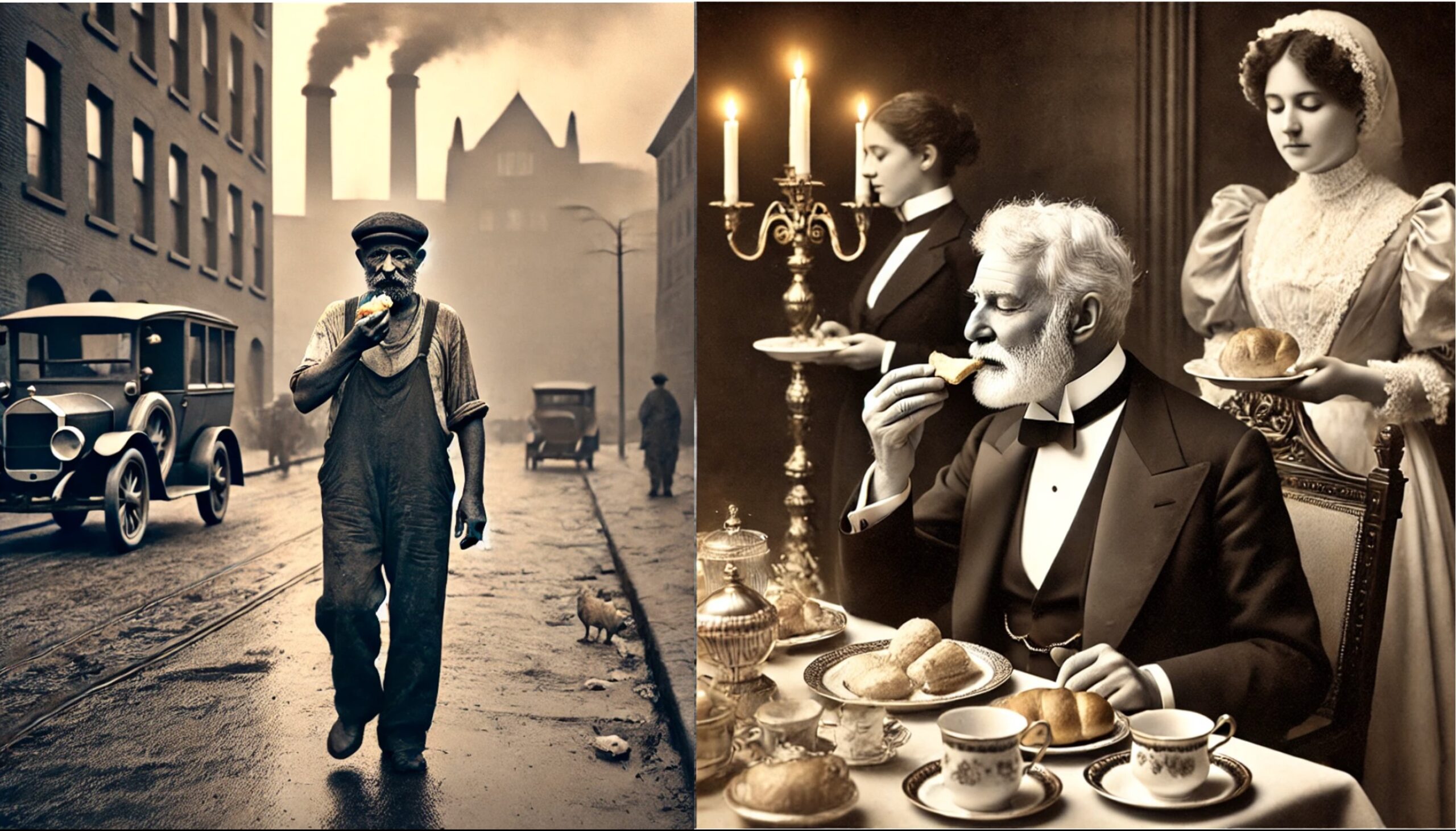

Arriving at the dining room he gives the freshly baked bread, bacon, sausages, cheese and fruit set along the sideboard a cursory glance knowing that Jack will have ensured all is in readiness. He sits at the head of the table facing the side-by-side portraits of his parents, William and Hannah Penn hung on the wall above that sideboard. While his feelings about his father were mixed, his admiration for his mother’s strength was without reserve. When his father had a series of strokes in 1712 that made him incapable of fulfilling his duties as proprietor of the Pennsylvania Colony, she assumed his duties and when their father died six years later, she officially became acting proprietor. When the eldest son from their father’s first marriage, a no-good drunk who once attacked a constable, sought to dismiss their father’s will and take over the colony, mother never flinched. She won the case, keeping control of the Colony in the family as his father had wished. She accomplished all this despite a life filled with tragedy. In addition to John and Richard, his parents had six other children, three of whom did not survive till their first birthday, one who died at three and another brother, Dennis, who died 14 years ago at the age of 16. Only their sister Margaret, two years younger than Thomas, was still alive.

Looking back at his father’s face, he knew full well how horrified he would be by what he and his brothers were about to do. As Jack serves him coffee, which he developed a taste for in the colonies, Richard and John enter. They exchange good mornings and Jack pours tea for Richard, who is still steeped in English custom, and hot chocolate for John, which is fast becoming the fashionable morning beverage in the colonies. After a bit of brotherly banter and Richard’s recounting of his stop in Philadelphia to visit their sister Margaret and her husband, they get down to business.

“So,” John began, “I assume, dear brother, that you haven’t traveled all this way to tell us that all the land we’ve sold over the last ten years has settled our debts.”

Richard shook his head. “Far from it, I’m afraid.”

Thomas placed his cup back in the saucer. “What debts remain?”

“More than 8,000 pounds.”

While not a complete surprise, this was still a shocking figure. It was half of the total debt Charles II had owed their grandfather which was settled by granting him the entire Pennsylvania province. That their only viable option to acquire those funds quickly was to accelerate the sale of those lands was sobering indeed.

Richard’s voice took on an ominous tone. “Brothers, I cannot stress enough how quickly we must make good on these obligations.”

Thomas and John exchanged a look. No elaboration was needed. Being shut out of the credit they needed for their businesses and the disastrous impact defaulting on their obligations would have on the social status, lifestyle and legacy of the Penn family name was too horrible to contemplate.

Richard continued. “You stated in your letter that our only path would be to liquidate more landholdings here in the Colony. Do you have a plan that will get us out of the box father’s treaty with the Lenape has put us in?”

Thomas and John exchanged another quick look before John answered, “We believe we do.”

Thomas pulled a sheet of parchment from a leather folder on the table. “This is a claim which will allow us to acquire an additional 1.2 million acres of land.”

Richard looked skeptical. “I don’t recall any such claim.”

“It’s connected to the 1683 treaty father signed with the Lenape.” Thomas explained.

John drummed his fingers on the table and nodded his head slightly from side to side. “It might be more accurate to say that this claim was inspired by the spirit of that treaty rather than a material part of it.”

This was the moment. They were telling Richard that this claim was a forgery, a deception that their father would never have agreed to be part of. How would Richard react?

“What makes you think the Lenape will accept this claim?”

Thomas’ shoulders relaxed. Richard’s concern was whether or not it would work rather than if it was legitimate. “Several factors are in our favor. Firstly, it’s clear that the Lenape don’t really understand the concept of owning land. Despite all that’s happened, they still see these treaties as agreements to share land rather than relinquishing their right to live on it. Secondly, we’ve negotiated a treaty with the Iroquois which includes this claim. Thirdly, our esteemed Land Office Agent and provincial secretary James Logan has produced a map which places the Lehigh River where Tohickon Creek is, which will make the amount of territory the Lenape will be giving up seem more palatable. Finally, the claim states that the distance a man can walk in a day and a half will form the south-eastern border of the claim.”

“Why is how far a man can walk important?”

Thomas and John chuckle and then John answers, “Because we control both who ‘walks’ and the path they take.”

Thomas elaborates, “We’ve retained Edward Marshall, Solomon Jennings, and James Yeates, purported to be the fastest runners in the entire province who will race along a trail that we’ve prepared. They will cover two to three times the distance the Lenape will estimate.”

Richard looks between his brothers with admiration that is still tinged with skepticism. “This all sounds very clever, but won’t it take time to get all this in place and to convince the Lenape to sign off?”

Thomas places his hand back on the claim. “Our faith in the strength of this claim is such that we’ve already begun to sell the lands in question.”

Richard smiles. “Brothers, it would appear we have a plan.”

“Yes,” Thomas says, “It would appear we do.”

The “Walking Purchase” or “Walking Treaty” is described by many historians as a “land swindle.” While it is but one of the many ways indigenous people were pushed out of Pennsylvania to make room for European settlers, the nakedness of its deception make it one of the most notorious.