Breakfast in Civilization Part V: Factory Life in 1900

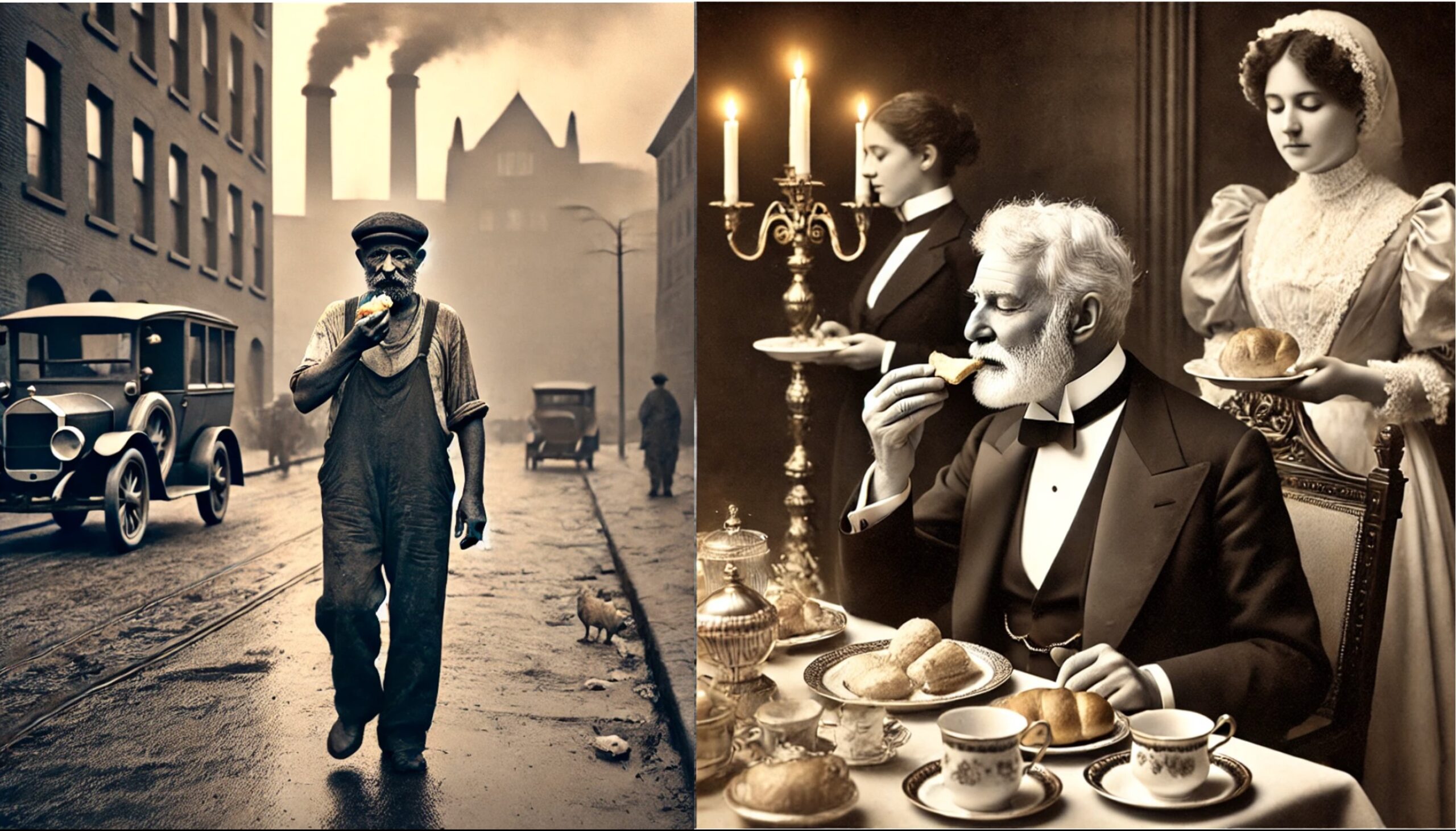

He wakes before dawn to head to the steel mill for another 12-hour shift, just as he does every single day save for July 4th, which Mr. Carnegie has deemed the only work holiday of the year. The bed, really just a cot, he rents from the company is shared with another worker who does the night shift. He walks down to the basement to wait his turn to use the toilet, which sits in an open room. When he first arrived, he was embarrassed to have to relieve himself in front of as many as a dozen other men, and deal with the sounds and smells the others made while he waited, but he’d grown used to it. His morning constitutional completed, he walks out of the apartment house, where nearly 300 steel workers live, or at least sleep, and into the street. Dawn is breaking but the constant stream of smoke from the plant blocks the sun. The streetlamps are still on and will likely go off for only a few midday hours before being turned on again to cut through the choking haze.

He pulls a bread crust from his pocket, stale now, as he bought it nearly a week ago, but it will have to do for his breakfast. The last chunk of that loaf, along with a piece of hard cheese, will be his lunch. He’ll buy a new loaf on his way home at the end of his shift. Making a loaf of bread and a hunk of cheese last for days is just one of the sacrifices he makes in order to send as much as he can of the roughly $10 he earns each week back to his wife and children in Hungary. They not only need the money to live, but to save up for their eventual passage to join him in America. His upcoming promotion to foreman will increase his weekly pay to $12 and he prayed every day that this extra money would allow his family to join him. Working every Sabbath and every holiday from Rosh Hashanah to Chanukah he worried that God might not hear his prayers.

Even in his early days, when he could not understand the words the townspeople used, he had no trouble understanding their harsh glares. He knew they blamed newcomers like him for everything from the loss of jobs to the “pox” and flu that raged through their now over-crowded city. One of the first English phrases he learned was “dirty Jew”, an insult hurled at recent Eastern European immigrants, whether Jewish or not. The townspeople seemed to resent having to look at grubby factory workers as they walked out of the shops where they purchased things they didn’t need at prices no mill worker could afford.

It was a little more than a year ago that he first came down the boat ramp, through the Ellis Island terminal and into a new world. After struggling to find work in New York, he heard there were jobs at the steel mills of Pittsburgh and managed to earn enough for a train ticket there. He was thrilled to immediately get hired at the Homestead Mill and even found some countrymen to help him assimilate. When he learned that he was hired to replace one of the seven men who were unable to work after a boiler exploded in the plant—three of those men sustained injuries which would prevent them from ever returning to work and two of them died—his sense of good fortune faded a bit.

He learned that accidents, including fatal ones, were a regular event at the mill. He always tried to be as careful as possible, but the fear that each day might be the last one where he could earn the money his family so desperately needed was constant. While he accepted this risk so he could provide for his family, there were boys, some as young as eight, who worked at the mill. The death of an eleven-year-old two months ago had shaken him deeply. The boy had become an orphan when his father died at the mill and was then sent to work in that same mill by the orphanage.

Once he arrives at the mill, he meets up with Benjamin the man who is training him to be a foreman. Even though Benjamin, as a black man, could never be a foreman himself, he knew more about how the mill functioned than most of the foremen did. Benjamin, at 47 was the oldest worker at the mill. The work was so physically taxing and dangerous it was said “there are no gray hairs in the steel mill.” He’d grown to like Benjamin, finding his stories about being a slave and then a sharecropper, which seemed to be more or less the same thing, in Virginia before coming to Pittsburgh harrowing but riveting. Benjamin came to Homestead, along with a number of other black men and recent immigrants, during the 1892 strike when mill manager Henry Clay Flick and owner Andrew Carnegie brought them in to keep the mill running and break the newly formed worker’s union. Workmates who had lived through that time related stories of the massive gun battle between Carnegie’s hired goons from the Pinkerton Detective Agency and the strikers. Dozens were killed, hundreds wounded, and the union was rendered powerless. There had been a couple of strikes since then, but they quickly folded and now workers were paid even less to work in even worse conditions.

Benjamin had been allowed to stay on, enduring the threats and taunts of his fellow workers, and had managed to stay able-bodied enough to keep working. Now he was entering the last phase of his working life, training a replacement who will make nearly three times his salary. Then, like a worn-out tool, he’ll be tossed aside.

* * *

“Mr. Carnegie, it’s seven AM”, his butler’s soft Scottish brogue rouses him. He sits up and slides the slippers already sitting by the side of the bed on, then stands and pulls on the lined silk robe being held for him. It’s dark and cold outside but the temperature in his opulent bedroom is comfortable as the staff tends the fires round the clock and light streams in from the electric lights in the hallway. When he purchased Skibo Castle in 1898 for eighty-five thousand pounds it was in a state of decay and desperately needed repair and modernization. He spent another two million pounds to expand and improve it, adding a swimming pavilion, a 9-hole golf course and his own power station so that his castle could have electricity decades before most UK homes would.

He is served a traditional Scottish breakfast, prepared by his chef and served by his butler, a footman and a kitchen maid. As he eats, he thinks about the telegraph he received yesterday from Charles Schwab, reporting on his meeting in New York City with JP Morgan. It appears the sale of Carnegie’s steel companies to Mr. Morgan will move forward. Now 66, Carnegie wants to retire from the business world to focus on philanthropy. He believes, as he once wrote, that “he who dies thus rich, dies disgraced”. This creates no small task for a man who will likely be the world’s richest after the sale to Morgan.

He dreams of the libraries and universities he will build to allow others to self-educate as he had. He imagines how the cause of world peace could be advanced with his millions. He bitterly resents being called a “robber baron” by everyone from ungrateful workers to Theodore Roosevelt, who had just become president after the assassination of William McKinley. He grimaced at the memory of J.P. Morgan talking him into supporting his effort to have the notoriously anti-business Roosevelt named as McKinley’s running mate where he would do less damage than he was doing as New York’s Governor. Look how that turned out. Carnegie’s burning desire is to be remembered for those libraries and not for a handful of clumsy workers who died in his mills, or in a gunfight–a gunfight they started–with the Pinkerton men Carnegie’s man Flick hired to keep producing the steel America needed to grow and prosper.

He feels immense satisfaction for how far his hard work has brought him. The son of a poor Scottish weaver, he immigrated to the US at 12 and found work as a “bobbin boy” replacing thread in a garment factory where six 12-hour days earned him $1.20 per week. He will be forever grateful to Corneal Anderson, who opened his 400-book library to him, where he read voraciously every Saturday night. By educating himself, working hard and not letting anything or anyone stand in his way, he continued to advance. When he was just 20, his father died suddenly, but he was able to take on the role of family breadwinner.

After transitioning to being a telegraph operator for a railroad, he rose to the position of superintendent of the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad at 24. Once there he learned how information about the business activities of the companies who used the railroad could lead to lucrative investments. Working for a railroad during the Civil War convinced him that steel was the future and with the fortune his stock trading produced, he bought his first mill. By making steel stronger, faster and cheaper than anyone else, his companies built railroads and skyscrapers, built America itself.

Innovation was a key to his success; he was the first to employ the Bessemer converter which allowed a relatively unskilled worker to harvest quality steel from pig iron. This dramatically upped production and lowered costs. Many of his workers, however, were unwilling to work hard and earn their way up the way he had. Constantly demanding higher wages and shorter hours, causing expensive accidents by not giving their work proper attention and then blaming mill management, or even Carnegie himself, for their mistakes. Their attempts to destroy his business by forming a union had to be firmly dealt with. His success in crushing the union had kept his costs low, his profits high and was a key to driving the $400M price J.P. Morgan would pay, thereby funding his philanthropic dreams.