Knowledge is Yummy

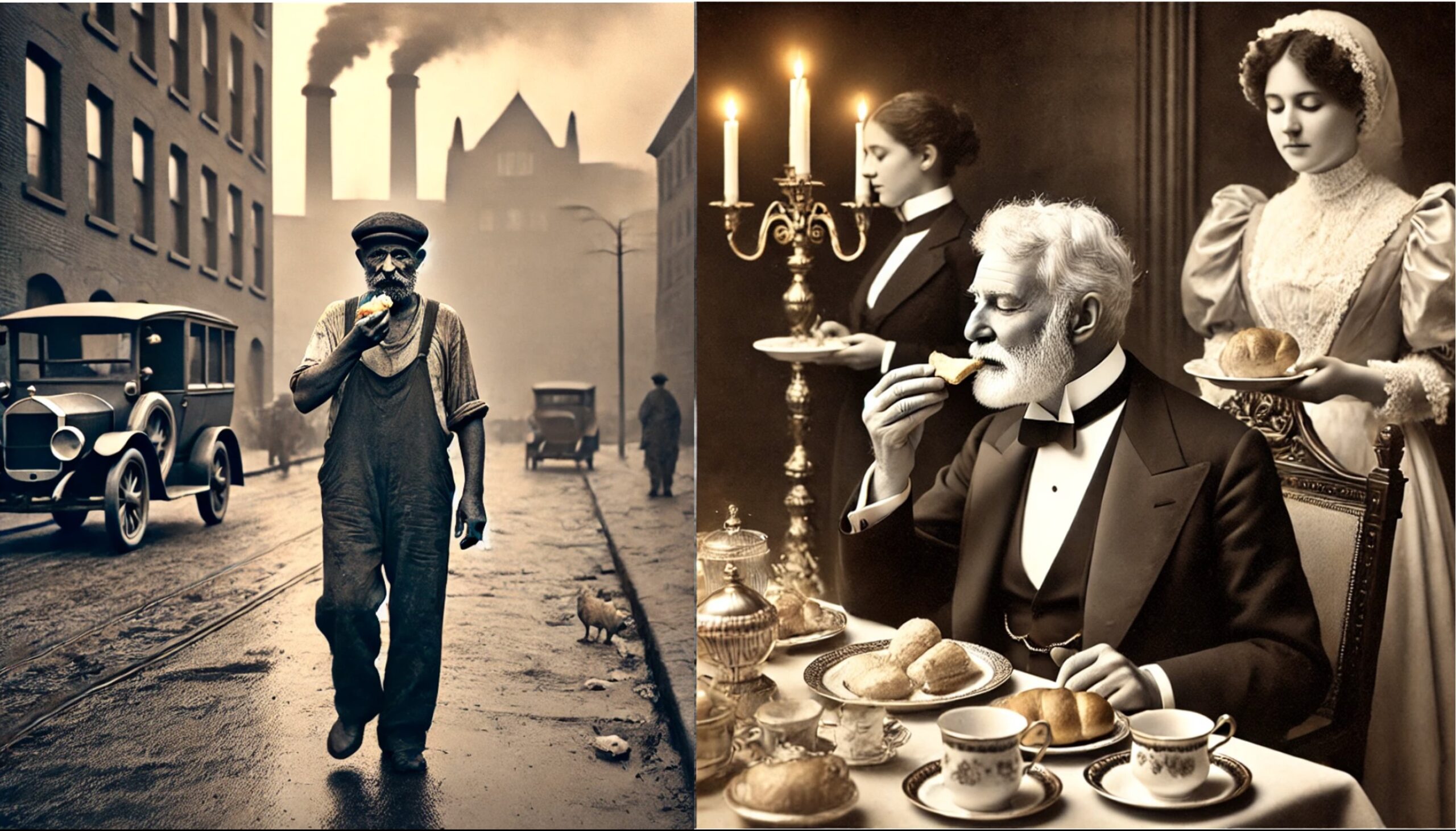

Throughout our history, humans have used reason and knowledge to constantly improve our ability to acquire food. This has been a key factor in our staggering growth and progress. From developing better tools and methods for hunting, to cultivating crops, to our massive modern food infrastructure, we leveraged our superior intellect and ability to collaborate in larger and larger groups to thrive like no other species. We do things like go for a bike ride, watch a TV show or read an interesting blog post rather than figure out how not to starve to death because of the dramatic reduction in effort required to obtain the calories we need to survive. We have created a world where too many rather than too few calories is our problem. This is a very new development.

While the historical curve of starvation and food insecurity shows steady improvement over the long haul, progress has spiked up dramatically in the last century[1]. Starvation, which for most of our history was a common cause of death, has significantly declined on a per-capita basis, especially since the mid-20th century[2]. This decline is largely due to advancements in agricultural productivity, often referred to as “The Green Revolution.” As recently as the 19th and early 20th centuries, famines and widespread hunger were common in many parts of the world, exacerbated by poor agricultural techniques and frequent wars. By the mid-20th century, many regions still suffered from chronic undernourishment, particularly in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

However, since the 1970s, global hunger has steadily decreased. According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the percentage of undernourished people globally fell from around 35% in the 1970s to less than 10% today. This decline was driven by improvements in food production, international aid, and better economic conditions. The Green Revolution, which introduced high-yield crop varieties and modern farming techniques, played a key role in increasing food availability. The soldiers in this revolution were not environmentalists, but scientists, engineers and logisticians. American agronomist Norman Borlaug, who is known as “The Father of the Green Revolution” led initiatives worldwide that contributed to extensive increases in agricultural production. The strain of “dwarf wheat” he developed is credited with saving over 1 billion people from starvation. Borlaug is one of only seven people in history to be awarded the Nobel Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. If I ever come up with a New Atenism prize for reason, knowledge and human progress Norman Borlaug would be on the short-list to get one.

While knowledge and reason have made tremendous progress, food insecurity remains an issue for around 9% of the global population. Far fewer people are starving now, on a per-capita basis, than at any other time in recorded history. However, challenges remain in eradicating hunger completely, especially in the world’s poorest regions.

There may be no better example of a “first world problem” than having access to too many calories rather than too few. The knowledge that made it so easy for us to acquire mouth-watering food at virtually any moment, however, has a dark side: the inverse relationship between the effort required per calorie for a food choice and how healthy a choice it is. Let’s compare a drive through fast-food hamburger and an organic salad you make yourself. The cost of the ingredients for the salad and the cheeseburger are both around $3.00[3] but while the salad requires a trip to the store, preparation and cleanup, the cheeseburger can be obtained while sitting in your car listening to Joe Rogan’s podcast. That cheeseburger costs about a penny per calorie and the salad roughly two pennies—and that’s only if you overdress it[4]. The salad is clearly the healthier choice, but it requires more effort and costs twice as much per calorie. Few perform this sort of cost/effort analysis when deciding to between a cheeseburger and a salad. It’s the mouth-watering flavor and deep, if somewhat guilt-tinged, satisfaction that comes from eating a cheeseburger that typically tips the scale.

The irresistible flavor of a cheeseburger is a product of human knowledge. All of the basic components, patty, cheese, bun veggies etc., were all developed through centuries of plant hybridization and selected animal breeding. If you set out to create a cheeseburger with only ingredients in their natural state, i.e., not manipulated by humans, not only would you not find a pickle tree or a bun bush, the closest you could get to a modern steer, would be a bison.

The genetic manipulation, and make no mistake that is what plant hybridization and selective animal breeding are, that made foods more palatable and plentiful was supercharged in the 20th century with advancements in food processing. In parallel, the emerging science of human cravings led to the design of foods which enflame those cravings more and more effectively. Our bodies were designed for a world where low-caloric density plants required far less effort to obtain than high-caloric density animal flesh and we now live in one where not only the savory animals, but an endless variety of irresistible calorically dense treats are pretty much always at our fingertips. Metabolic diseases like type 2 diabetes, gout and certain types of cancer[5], which used to affect only the rich, now disproportionately affect the poor. The other even darker side of modern food production is its disastrous effect on the environment. From massive pesticide and chemical fertilizer use to being the single largest man-made contributor to climate change[6].

Okay, so all that fabulous food-acquiring knowledge we’ve acquired through reason has saved billions of lives but is also killing us because those cheeseburgers taste so damn good, are so easy to get and lead to deadly diseases. And oh yeah, its fingerprints are all over global warming. What good is all that knowledge if it’s making us fat and sick? Wouldn’t it be better to stick with nature and have a reason and knowledge free salad?

That salad seems like the ultimate “all-natural” meal. Its fresh vegetables and organic label promise it was grown without synthetic pesticides or fertilizers. However, even that simple salad represents centuries of human knowledge and intervention. The lettuce, tomatoes, and cucumbers in that salad have also been selectively bred for generations to enhance their flavor, size, yield, and resistance to disease. The wild ancestors of these crops would be almost unrecognizable today. Hybridization—crossbreeding different varieties of plants to create new strains with desirable traits—has played a huge role in modern agriculture. This knowledge has allowed farmers to produce more food on less land while still maintaining the organic label.

The vast majority of organic produce in the United States is produced by large, corporate farms. About 88% of organic sales take place through conventional supermarkets and natural food chains, which rely on large suppliers to meet demand. This means that much of the organic produce sold in the U.S. comes from large-scale operations that, while organic, often resemble large, conventional farm systems in their cultivation and distribution. These large organic farms use mechanized equipment, monocropping, and high-volume production to supply organic fruits and vegetables to supermarkets like Whole Foods and Kroger. Although the crops are grown without synthetic chemicals, these farms operate on a scale that raises questions about sustainability. In fact, research shows that larger organic farms tend to use fewer agroecological practices, such as crop diversity and natural pest control, compared to smaller farms.

Even getting organic produce to your local market involves a surprising amount of knowledge and infrastructure. Organic vegetables must be harvested, stored, and transported in ways that preserve their freshness without the use of preservatives or artificial ripening agents. In some cases, organic produce is shipped hundreds or even thousands of miles to reach consumers, raising questions about its environmental impact. The logistics behind keeping these products fresh and available year-round requires a deep understanding of food science, packaging, and distribution networks.

My purpose here is not equate a salad with a McDonald’s cheeseburger, but rather to point out that there are elements of our food progress which have been incredibly helpful to humans but has also produced some unintended consequences. The spirt of reason is embracing the helpful and rejecting the harmful which, in this context, means embracing our ability to provide food on a massive scale and our ability to reduce the effort required by everyone to obtain food while rejecting foods that are killing us and our planet. This may sound like a false choice, or an impossible dream, but reason is already hard at work on solving this puzzle.

Lab-grown meat, technology that still in its infancy, offers a way to produce meat products without the environmental and ethical concerns associated with traditional animal farming. It has the potential dramatically reduce land use, water consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods are developing plant-based products that closely mimic the taste and texture of traditional meat. These alternatives are already more sustainable and often have fewer calories and saturated fats compared to conventional meat.

Local hydroponic farms, which grow food without soil, and vertical farms, which optimize space and resources, are helping cities grow fresh, nutritious vegetables in controlled environments. This can significantly reduce transportation costs and environmental impact while maintaining a consistent supply of fresh, healthy produce. Growing these facilities to a scale where they can provide truly local sources that don’t require long-range transportation will dramatically increase availability of fresh, healthy foods while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Researchers are working on biofortification, the process of breeding crops to increase their nutritional value. This has the potential to make mass-produced foods as nutritionally dense as salads. Another innovative approach to crafting healthy, sustainable food ingredients that are scalable for mass production is precision fermentation which creates dairy alternatives and nutrient-dense ingredients.

These technologies show promise for creating nutritious, sustainable, and delicious food options that could bridge the gap between the ease and appeal of cheeseburgers and the nutritional benefits of salads. In the meantime, and if you have the means, your best bet for your own health and our planet’s is that salad, especially if the ingredients are grown locally.

[1] “Hunger and Undernourishment” — Hannah Ritchie, Pablo Rosado and Max Roser for Our World in Data 2023

[2] “Famines” — Joe Hasell and Max Roser for Our World in Data 2013

[3] A McDonald’s cheeseburger currently costs an average of $2.79 in the US and a single serving of organic greens

cucumbers, tomatoes and carrots along with a bit of olive oil and vinegar should cost you close to $3 depending on where you shop

[4] My wife claims I habitually under-dress salad

[5] “Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of Cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis” – by Katherine Esposito, MD; Paolo Chiodini, PHD; Annamaria Colao, MD; Andrea Lenzi, MD; Dario Giugliano, MD. American Diabetes Association October 2012

[6] A 2015 World Economic Forum study found global food systems were responsible for about 25% to 42% of global greenhouse gas emissions.