Religion Who Needs It?

The first person outside of my nuclear family with whom I shared my desire to create a religion of reason asked me “Why not just have everyone buy a science book?” At the time I made a snarky comment about how science books are always checked out of the library, sold out at bookstores, and you can’t go anywhere without bumping into somebody with their nose in a science book, but his question stuck with me. If the goal is to foster a deeper belief in reason, what value could a religious framework offer? There has been a lot of conflict between reason and religion over the ages and many consider them diametrically opposed or even mortal enemies. Isn’t founding a religion of reason a bit like opening a firing range for pacifists?

Last week’s post discussed how skeptics pit science against religion’s cosmological ideas and its checkered history against its moral ideas. The literary point of the religious-critical spear is authors like Richard Dawkins, who described religion as “infantile,” in his book “The God Delusion”, the late Christopher Hitchens, whose book “God is Not Great” featured the subtitle “How religion poisons everything,” Daniel Dennett, who passed away in April of 2024, said believers have “dedicated their lives to an illusion” and Sam Harris, who in “The End of Faith” likened religious faith to mental illness. Are these so-called “New Atheists”, who many consider to be co-captains of team reason, right to ask the question: “Religion, who needs it?”[1]

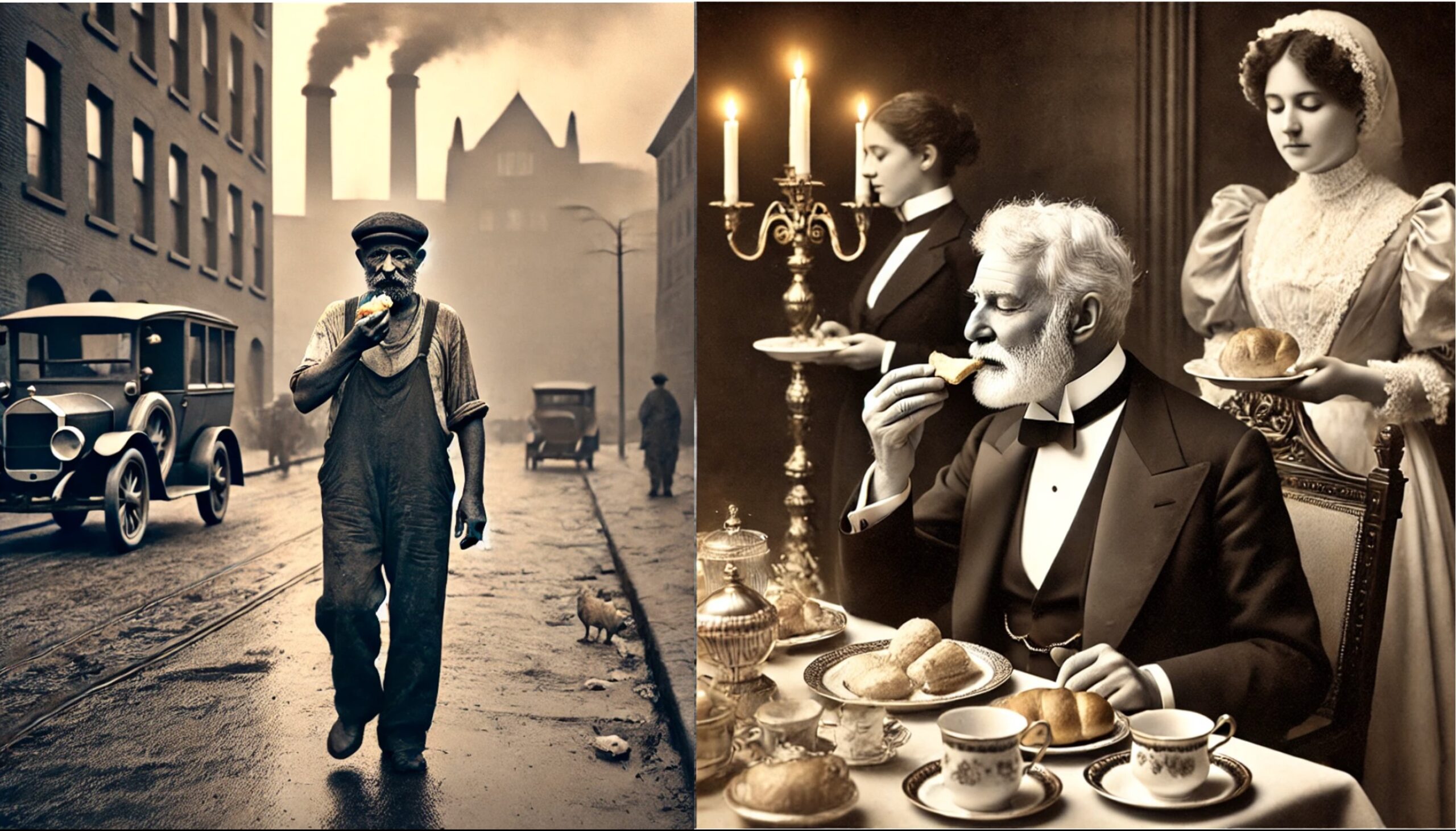

As we also saw last week, the literal answer to this rhetorical question is pretty much everyone. Religion is still an important part of people’s lives. It can provide comfort and community and foster positive personal traits like humility, empathy and gratitude. A 2019 study from Pew Research showed that people who are “actively religious,” attending services at least once per week, are happier and healthier than non-active believers and non-believers. With 85% of the world’s population identifying with a religion, a similar number believing in God, and the fostering of communal effort, positive personal traits and better health and happiness outcomes. Evolutionary psychologists, like Jonathan Haidt, argue that religiosity is a naturally selected trait because the communal action it fostered gave believers an advantage over non-believers. If humans had adopted one religion with the same central narrative and interpreted it the same way, it would still be a net-positive for human progress but there are hundreds of differing stories with thousands of different interpretations.

Over the past 300 years, and especially the last 100, religion’s contributions to progress have not only waned, but many religious leaders, stung by the sharp reduction in their authority, openly advocate moving backwards. Religious skeptics and critics have long argued that religion is a net detractor of human progress and the more our advancement takes place outside of the religious domain, and the harder religious leaders try to pull us back, the weaker any counter argument becomes.

So where does all this leave us? New central myths are emerging which reduce the scope of “how things are” to accommodate what we’ve learned. Moral ideas (what things matter) are moving away from top-down interpretations from authority towards more common “golden rule” oriented values. Supernatural notions, still believed by most people, are now spread across a wide range of religious/spiritual beliefs and practices. All this has created an even greater number of groups with evermore conflicting stories. We still have people holding fast to outdated interpretations of religious texts as the last word for facts and morals. We have people who modify traditional religious cosmological ideas to accommodate what reason has revealed while still following its moral teachings. We have people who reject traditional religious authority either to follow a new religious practice or spiritual path. We have people who sit somewhere between these groups following some combination of their elements.

Religious belief is rooted in our deep desire for certainty. The march of reason has injected a lot of unsettling uncertainty into the mix. Reason’s power comes from its ability to spread knowledge acquisition and verification across many millions of people, but this requires us to be humble about our own level of knowledge and to believe in reason. We’d rather believe we know the answer than admit we don’t. Despite this, more and more people are less and less comfortable with accepting religious authority’s answers. We want to, need to, believe in something. Ironically, it is reason that despite its tenant of questioning everything, that can provide the certainty we so desire. The belief that reason created the knowledge which has powered the advancement of our species creating the longer more comfortable lives we enjoy is supported by mountains of evidence. The power of reason is one of the few things we can be truly certain of.

How does the process of reason work and what exactly is reason’s power? Physicist David Deutsch in his book “The Beginning of Infinity” describes knowledge as our best explanation, what is most likely to be true based upon the evidence we currently have. The process of reason is an on-going search for better explanations which requires we always are open to the idea we could be wrong. In “The Beginning of Infinity” Deutsch compares the Greek mythical explanation for winter to our current best explanation. In the myth, Hades kidnaps Persephone, the goddess of spring, and only agrees to let her go home for part of the year. Demeter the goddess of the Earth and Persephone’s mother, is sad when her daughter is gone and makes the Earth cold and barren during winter and then bright and sunny again when they’re reunited each spring. This myth provided a suitable explanation for why it’s cold in the winter only because ancient Greeks were unaware that winters are warmer in the Southern hemisphere. There are countless other myths and legends about what causes winter, but our current best explanation, that seasons are caused by the Earth’s tilt and orbit, is now accepted as the best one, most likely to be true, and has united us. We’ve progressed from having many conflicting stories about the cause of winter, to one that unites us based on knowledge developed by the process of reason.

There are many other examples of phenomena which once had many differing mythological explanations which have now coalesced behind our current reason-driven best explanation. There are also, sadly, many examples of highly supported explanations that are still rejected by some in favor of mythological, religious, or supernatural ones. In a future blog post, I’ll delve into why we reject reason to believe the things we do and will make the case that it is reason itself we should believe in.

Can a religion of reason exist? If one is to use reason as the basis for a belief system, it requires restricting one’s beliefs to those which are supported by enough evidence to be considered our best explanation. With our current knowledge, our known knowns, one cannot have a highly supported belief about what the universe was like before the big bang, how non-living matter first became living or in a supernatural parental God who created the universe, hears your prayers and intervenes in your life.

In my book I define the first age of religion, the period leading up to the Enlightenment in the 17th century, as its infancy, where lack of knowledge created a near total dependence on authority for answers to the unknown. The post-Enlightenment age, which we are still in, can be thought of as religion’s adolescence. In this age, knowledge grows, and authority begins to be questioned, but many still hold the belief systems of their clique and their own largely ill-informed assumptions in higher esteem than reason and evidence (This will sound familiar to anyone who has presented a teenager with peer-reviewed studies showing that excessive use of social media and messaging apps shortens attention span.) I will make the case that humanity is ready for an adult religion. That our knowledge has developed, like a 20-something’s prefrontal cortex, such that we can now place our belief in what we know and how we know it rather than myths and stories that fill in the gaps of what we don’t know.

Acknowledging the limits of our individual knowledge and being deeply grateful for the blessings and prosperity our massive collective knowledge has brought us will facilitate our species’ amazing progress. New Atenism invites you to join a religion which can unite us behind what reason has revealed as most likely to be true rather than behind what an authority claims to be. A religion with a concept of the divine that is not only supported by reason, but requires reason to reveal it. A religion that venerates a life giving and life sustaining power we know exists that serves as a model for how we can progress individually and collectively. Next week’s blog post will explore this view of God and following weeks will reveal this life-giving power, even though you’re already fully aware of it, and how it serves as a model for personal and collective progress.

.

[1] To be fair I don’t think any of these gentlemen ever actually asked this question, even rhetorically, and all lament that believers far outnumber non-believers, so I’m using “who needs it?” colloquially as a way to say something has little or no value which sums up the New Atheist position on religion.