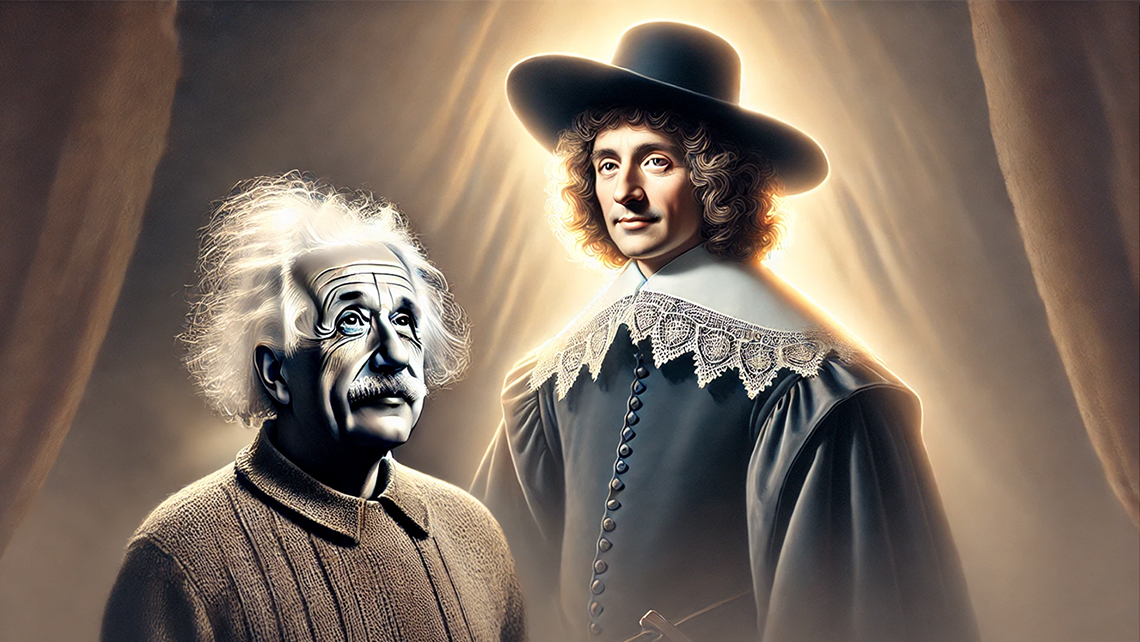

The God of Spinoza & Einstein

“My views are near those of Spinoza: admiration for the beauty of and belief in the logical simplicity of the order which we can grasp humbly and only imperfectly. I believe that we have to content ourselves with our imperfect knowledge and understanding and treat values and moral obligations as a purely human problem-the most important of all human problems.” – Albert Einstein

That Einstein is so often quoted, and so often misquoted or has things he never said attributed to him, is understandable. Who wouldn’t want to have the support of someone who many believe was the smartest person who ever lived? I’m no different, but that quote above is not only something he did actually say, it’s something he truly believed. Einstein had a full-blown man-crush on Spinoza, even writing him a poetic tribute.

“How much do I love this noble man

More than I could say with words

I fear though he’ll remain alone

With a holy halo of his own…

You think his example would show us

What this teaching can give humankind

Trust not the comforting façade:

One must be born sublime” – Albert Einstein 1920

Luckily the whole revolutionizing our understanding of the universe thing worked out so Albert did not have to depend on his poetry to pay the rent. So, who was this Spinoza character and why is his view of God so popular with no just Einstein but many other champions of reason?

In order for us to “know God,” Spinoza believed there was only one way: reason. Only by applying logic and critical thinking to things we can perceive do we move something from the unknown to the known. Learning more about Nature is the process of building an evidentiary bridge between thought and extension, bringing an idea or concept into the real world. The idea that space and time are connected once existed only in the thought domain and only in the brain of one person, Albert Einstein[1]. This idea was brought into the minds of others when Einstein published his theory of special relativity in 1905. Over time, countless experiments were conducted which validated and verified this theory and led to an incredible array of innovations which have dramatically changed the world. This is the story of progress, building bridges between thought and extension.

There are still a whole lot of things we don’t know. For example, what happened, if anything, before the Big Bang? To believe in Spinoza’s God is to accept this as unknown because reason has not yet revealed this attribute of God, this part of Nature. While there are some compelling, and competing, theories, no real evidentiary bridge between pre-Big Bang ideas and reality yet exists. While reason is being employed, including referring to our ever-increasing knowledge of the early universe, the “what happened before the Big Bang?” question is still firmly planted in the thought domain. This is not to say that all pre-Big Bang ideas are of equal value as some are connected to existing knowledge and/or are supported by reasonable arguments rather than just being a compelling story.

When we build a bridge, we learn one more thing about Nature, about God. Spinoza rejected all “God talked to me” stories, believing that divine revelation could only be accomplished through reason. While philosophers who predated Spinoza, including Plato, Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, believed reason played a key role in understanding the divine, Spinoza’s combining this notion with a total rejection of an active agent God that exists outside of nature was both revolutionary and powerful. The power lies in believing in what we know, in those ideas and concepts for which there is a evidentiary bridge, and in accepting what we don’t. Placing reason over the claims of religious authority made Spinoza a key figure in reason’s revolution, The Enlightenment.

Einstein also rejected the idea of a personal God who hears and answers prayers, calling it “an anthropological concept which I cannot take seriously.” Like Spinoza, Einstein believed that the only way God is revealed to us is through the narrow window of our perception, using our limited cognitive capabilities.

Unlike the typical “4 O’s” God (omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent, omnibenevolent) Spinoza’s definition of God has an evidentiary bridge. If God/Nature is everything that ever has or ever will exist then one only has to accept that there is such a thing as existence. Even philosophers who argue that the only thing that is certain to exist is their own mind, think Descartes’ “I think therefore I am,” concede that something exists. Spinoza’s rejection of an active agent 4 O’s God who hears prayers and intervenes in human affairs is probably what got him excommunicated from the Jewish community of Amsterdam in 1656. Spinoza’s placing reason above authority, specifically religious authority, is what made him a fundamental Enlightenment thinker. To Spinoza, unknown parts of Nature, of God, remain unknown until and unless they are moved to the known via reason. This is in stark contrast to virtually all mythological and religious traditions which make cosmological claims about how and why things are, as well as moral claims about what things matter, which went far beyond what was known at the time of their inception.

Spinoza defined God as being Nature and the individual things we are able to perceive in the world as expressions of God. He saw these perceivable “modes” as windows into God’s “attributes”. Ants, oceans, stars and galaxies, as well as all human thought and knowledge are all finite things (modes) which have been modified by their interactions with other finite things all governed by the infinite laws of nature. An ant, for example, needs a mommy ant and a daddy ant and a person can’t produce a thought without a functioning brain. These things are finite and dependent on other things, each a link in a long chain of causation of things modifying other things. The laws of nature which govern how finite things are created and modified, however, are infinite, unchanging and independent, not reliant upon anything else. All human knowledge, thoughts and concepts are finite pieces of “infinite intellect.”

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy” – Hamlet Act 1 Scene 5 – William Shakespeare

Spinoza’s identification of thought and extension as two of the ‘infinite attributes’ of God frames both the process by which reason brings ideas into the real world and its inherent limitations. He believed that there are an infinite number of ways to perceive Nature, but because we mere mortals have access to only two of them, the scope of the unknown is dramatically, infinitely, expanded. This aspect of Spinoza’s definition of God is incredibly important and often overlooked. While religious authorities often ascribe the idea that God is infinite and beyond our understanding, they typically use this mystery as supporting evidence for their particular doctrine. Rather than accepting the discomfort of doubt and acknowledging the unknown, they opt for dogmatic certainty. Although we do not know—and likely never will know—whether Spinoza was right that there are an infinite number of ways to perceive, reason has shown that we can bring things lying outside our perception into the realm of our understanding.

One key departure I make from Spinoza lies in his concept of “substance”—a thing which must exist, is self-caused, and underlies all of reality. Spinoza identified this necessary substance with God or Nature, believing that strict determinism required such a being to explain the existence of everything else. While this is a coherent and even elegant solution, it goes a step beyond what we can claim with confidence today. Modern physics—especially quantum theory—has introduced apparent indeterminacy into our understanding of the universe, and even the question of whether the universe had a beginning or has always existed remains unresolved. So, while Spinoza’s commitment to causal explanation still inspires, I stop short of asserting that there must be a self-caused first substance. For now, the origins of existence are beyond our current knowledge, and might always be.

God or Nature with a capital “N.” All that ever has or ever will exist, all that is known, unknown and unknowable. Only through reason can we come to know God. Spinoza’s definition is more than a theological concept, it’s a way of looking at reality and recognizing the limits of what we can perceive and understand. It is to believe in the power of reason to reveal God/Nature to us while acknowledging that there many aspects and attributes of Nature beyond our perception and understanding. While the whole-hearted acceptance of a faith tradition’s dogma and doctrine provides a comforting certainty, it is most often illusory. We can, however, be certain that reason is the only path we’ve found to reveal Nature to us.

Spinoza is seen by many as the father of pantheism because equating God with nature is a foundational pantheistic belief. While pantheism might be the belief system we have a name for that best fits Spinoza’s concept of God, pantheism has come to mean a lot of different things to different people. Most pantheists identify the physical universe and its natural laws as being divine, but often do not include thought, concepts and knowledge. Some pantheists see God as having agency , or as being “good ”, which leans towards a 4 O’s God concept. Spinoza’s concept of an infinite number of ways to perceive is not part of the pantheist mindset which is typically rooted in our limited perceptions of the natural world. This is why that capital “N” is so important. While Spinoza’s philosophy has been described as “Spinozism”, “naturalistic monism” and “substance monism,” among other things, if the only categories you could choose from were theist, atheist, deist or pantheist, pantheist would come the closest to aligning with Spinoza’s concept of God.

The concept of God and Nature being one and the same will likely not sit right with many of you, as the traditional 4 O’s view of God is so deeply ingrained in our culture. Some scholars claim Spinoza was an atheist which seems odd given how much time he put into defining God. Claiming Spinoza was an atheist amounts to not accepting his definition of God, that one has to believe in a 4 O’s God for it to count. I find it curious that these atheists are untroubled about being in lockstep with the religious fundamentalists who excommunicated Spinoza for not accepting their definition of God. A core principle of reason and the Enlightenment is the rejection of authority, specifically religious authority, so why would a reasonable person accept religious authority’s definition of God? Spinoza didn’t reject the existence of God, he brought God out of the imagined supernatural realm and into the reality-based community–a far more powerful idea than mere atheism. Spinoza’s God is the God we know exists because we use reason, our truth-searching superpower, to verify that knowledge.

However religious or non-religious your background, you might find yourself uncomfortable using the word “God” in this way. If so, “Nature” with a capital “N” can be substituted. While God and Nature will be used interchangeably and conjointly in this book and the religion it founds, one can be a practicing New Atenist without ever saying the word God. In either case, we’re talking about the same thing– everything–which we should all comfortably agree does in fact exist.

The unifying effect of Spinoza’s God goes far beyond any imagined 4 O’s God. There are an infinite number of possible stories, but the truth is singular. Reason is the best truth-finding tool humans have come up with and the more we learn about the universe(s), and ourselves, the more we can, or at least should, agree upon. The further God moves from the unknown to the known, the greater our ability to line up behind one true story rather than remain scattered across an endless horizon of conflicting narratives.

[1] There are those who argue that Einstein’s former math professor, Hermann Minkowski, was thinking about relativity at around the same time Einstein published his theory of special relativity in 1905. Minkowski later provided a mathematical framework for Einstein’s theory in 1908, which helped to solidify and extend its implications.